What Is The Most Common Form Of The Blues

Is there an importance in classifying blues genres?

One question that comes up from time to time is what form of the blues is most common.

As a general note, and a more spiritual level, I’d say the common form of the blues lies in the natural human condition of suffering. I mean this in an honest, everyday type of way; whether it’s in the form of getting an unexpected tax bill at the end of the month or saying goodbye for whatever reason to someone you love, the blues form kernel is prevalent in all strains of music. The unique African-American take on expressing this condition, in my humble opinion, is in channeling those feelings into grooves which make your body sway like unlike any other music, licks which seem to say “times are tough but it’s alright”, and a communal togetherness in playing with band-mates and for audiences which brings everyone together with a common sense of existence.

Blues music often isn’t defined by technicalities like chord structure

With that being said, playing blues does not mean strictly and academically playing a 12 bar blues progression, devoid of feeling. In fact, one can play blues with the depth of the ocean and never stray from a single chord. On the other hand, common pop artists may sing over the 12 bar blues and you know that — despite the fact that, yes, technically they’re playing a blues progression — it sure as shit isn’t the blues.

It’s just a feeling which, “if you know, you know.” Some people never know — it’s true. It’s a gift to be able to discern that sense of the blues form, and not one to be wasted. This is why often times you can listen to Charlie Parker or Art Tatum, artists who “analysts” may not call blues musicians, yet they play nothing but the blues without playing strict progressions — it’s in that feeling; the twist or the slant they imbue to the phrasing.

As such, this is all to say that the remainder of this post, answering what the most common form of the blues is, is largely a moot point. Anything can be the blues. However, there’s certainly a place for nomenclature and calling things certain things, so certainly it’s also useful to identify Delta Blues from Country Blues or 12 Bar Blues from 8 Bar Blues, though this preface was simply to say to take it with a grain of salt! Without further ado, here are some broad ways to color these terms.

Delta Blues

Often characterized by jagged guitar lines, sneaking slow-to-medium paced tempos, and moaning vocals, Delta Blues is among the most celebrated genres of blues for its influence on so many genres today.

By jagged guitar lines, this refers to the treble-side riffs that are often played with a slide or with fretted-fingers, which often solo within the gaps of vocals. The aggressive treble-side lines and piercing slides are often irregular because they’re improvised and almost disturbing in their dark quality, since they’re often complementing dark subject-matter of the songs’ lyrics. The bassline work of Delta Blues can often take a hybrid approach of Piedmont Blues (that is, alternating basslines) or Texas Blues (monotonous basslines which form a bouncy basis for the song). Also, the basslines can be neither — lines which instead fit like a perfect puzzle-piece within the structure of the treble-side lines, or improvised similar to the treble-side.

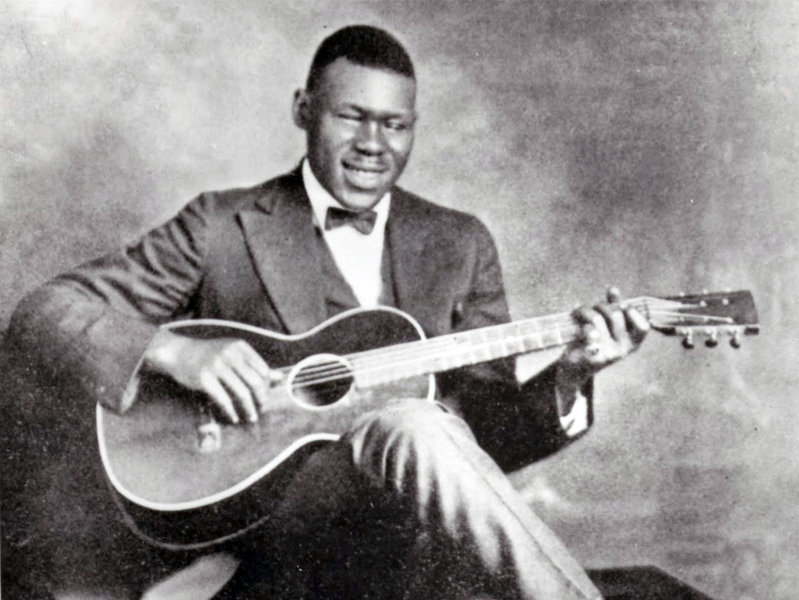

For the hybrid Piedmont / Texas approach, Charlie Patton would employ this strategy very much, being an earlier player when the Delta sound was at that point most likely less defined. For the archetypal jagged sound with improvised treble and bass-side lines, King Solomon Hill is a fine example. For the kind of puzzle-piece bassline approach, Willie Brown represents this well.

Piedmont Blues

This type of blues is characterized by a more ragtime, piano-type influence, with bouncy alternating basslines that mimicked ragtime players such as Jelly Roll Morton and James P. Johnson. Tempos are typically, though not always, more brisk with Piedmont Blues versus Delta Blues, since the players were often marked by their facility to play these basslines at high speed, while singing and playing treble lines simultaneously.

Often times, to further their demonstration of prowess, players would do things like “displace” the bassline (instead of simply playing root-octave-root-octave on the bass side, they’d play root-root-octave-root, etc). In this case as well, piano players such as James P. Johnson and Willie “the Lion” Smith were pioneers of these “beat tricks” which guitar players readily adopted. The high-degree of technical respect these Piedmont players commanded was in their ability to not only add treble lines while playing these bass riffs, but also while navigating more sophisticated chord progressions. Their added knowledge of progressions beyond 12 Bar Blues allowed them to add great depth to their repertoire.

Fine examples of Piedmont players include Blind Blake and Blind Boy Fuller. Each of these musicians would play with that bouncy, brisk tempo, ragtime-like bassline accompaniment, doubling lead lines, and more complex chord progressions. To be quite fair in this discussion, this is partly where some lines blur, since artists like Charlie Patton did play some of this category (such as Spoonful Blues), but you can certainly hear even in that song, Spoonful Blues, that there’s still some Delta jaggedness and purposeful messiness (which adds that Delta edge) which is less identifiable in the cleanly, never-miss-a-beat style of Piedmont.

Country Blues

Whereas Delta Blues seems to have that edgy style — that coolness, and Piedmont has that “guitar-gunslinger” quality, Country Blues is perhaps simpler and more down-to-earth. There’s often not very much virtuosity to it, and many of the musicians who might be categorized as Country Blues players were probably just normal people who played some guitar. In other words, it’s a simpler, more-raw folk look at the blues.

Technically speaking, this could mean simpler strumming patterns (in some cases no patterns at all, just a kind of white-noise strumming during vocals), and also not very much complexity in terms of lead-lines, if any. It might even be possible to say that Country Blues is simply raw, African-American folk music, songs that were often sung at home for entertainment, and so on (not that these other genres weren’t part of that also!).

Examples of players who come to mind include the likes of Blind Joe Reynolds, Lead Belly, or Peg Leg Howell. Again, this categorization is not black and white since Lead Belly also played songs like Matchbox Blues which you could quite easily identify as Texas Blues and so on. This is just meant to say that a decent part of their recordings could perhaps be categorized under this simpler, folk label of Country Blues.

Texas Blues

Texas Blues is easier to identify since it’s got some more defining features than other genres. The major identifier of Texas Blues is that it’s got that rough, knife-like monotonous bassline which often, messily, runs through the song. I say messily since often times players are playing their guitars with such force that they hit the “wrong” strings, or play extra beats because they’re so in the moment. On top of that, Texas Blues players also often play with the bottleneck slide on the treble-side. In total, often times they’re playing these monotonous basslines with treble-side solos and fills.

A handful of great examples of this style exist — the aforementioned recording of Lead Belly playing Matchbox Blues, Lightnin’ Hopkins, Robert Johnson playing 32-20 Blues, and Mance Lipscomb playing Jack O’ Diamonds. Sure enough, all these players spent substantial portions of their life in Texas.

In many ways, Texas Blues shares much with Delta Blues. The imprecise, jaggedness of the playing, the edginess of the entire mood. Main differences are perhaps that Delta Blues is often slightly more pensive (whereas Texas Blues is more pulsating) and also that Texas Blues strongly adopts that monotonous bassline as mentioned before.

Hill-Country Blues

A real crowd-favorite type of blues, and one that really can’t be faked (although none of these can really be faked), is Hill-Country Blues. Where Texas Blues is gruff & rough, Delta Blues is filled with depth and jagged color, Hill-Country Blues is funky — with almost magical riffs that make you want to dance.

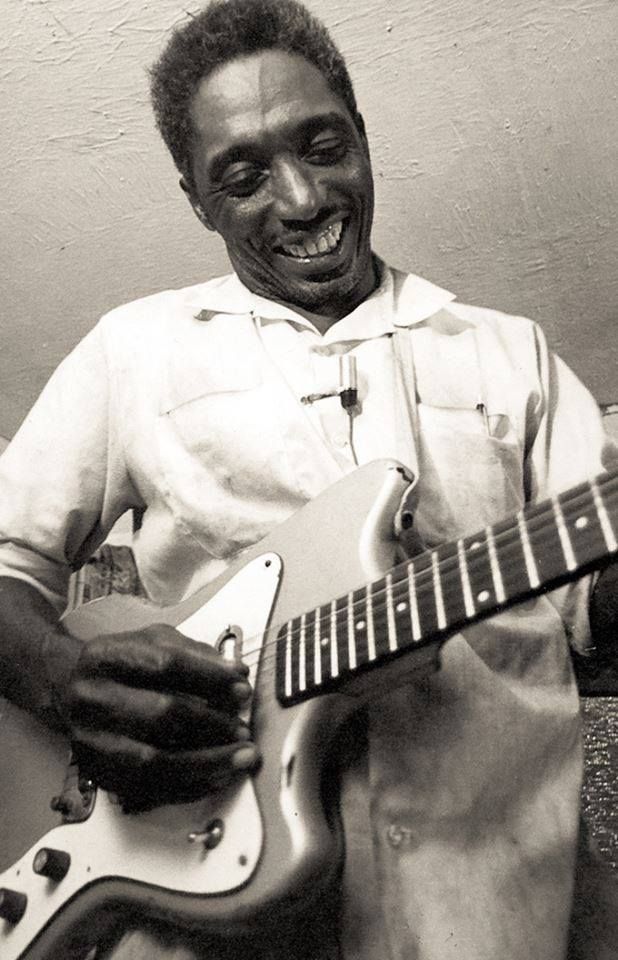

Straight-away, great examples of this are R.L. Burnside’s recordings of See My Jumper Hangin’ On the Line and Poor Black Mattie. Playing those songs’ riffs, it’s truly not just a matter of learning technique and mechanically executing the well-oiled gears of bassline riffs and treble-side riffs that fit together like a working machine. Instead, it just has to be played with that spirited, easy yet propelling feel. It just can’t be faked.

Two of the archetypal examples of this style are R.L. Burnside and Junior Kimbrough. Just a short Youtube session of their work illustrates this unmistakable form of blues.

Chicago Blues

A kind-of younger cousin or child of these older forms of blues is Chicago Blues. In fact, the original musicians who formed the Chicago Blues sound, people such as Big Bill Broonzy and Muddy Waters, were steeped in Texas Blues and Delta Blues abilities. Bringing that edgy sound to this newer urban environment, given the later times of the 1940s and 1950s when the electric guitar was more prevalent, they played those sounds through amplifiers, transitioning from acoustic to electric guitars. Perhaps being in that louder, urban environment (and also possibly more money) they played with large bands also: adding a harmonica, drums, bass, and piano to the mix.

Also, the mood was different. As Kevin Moore, a blues musician put it, “you have to put some new life into it, new blood, new perspectives. You can’t keep talking about mules, workin’ on the levee.” So a whole paradigm-shift both in the technicalities of the playing (since with a full band you were free to play just lead lines with the guitar, for example), as well as the meaning behind the music occurred with Chicago Blues.

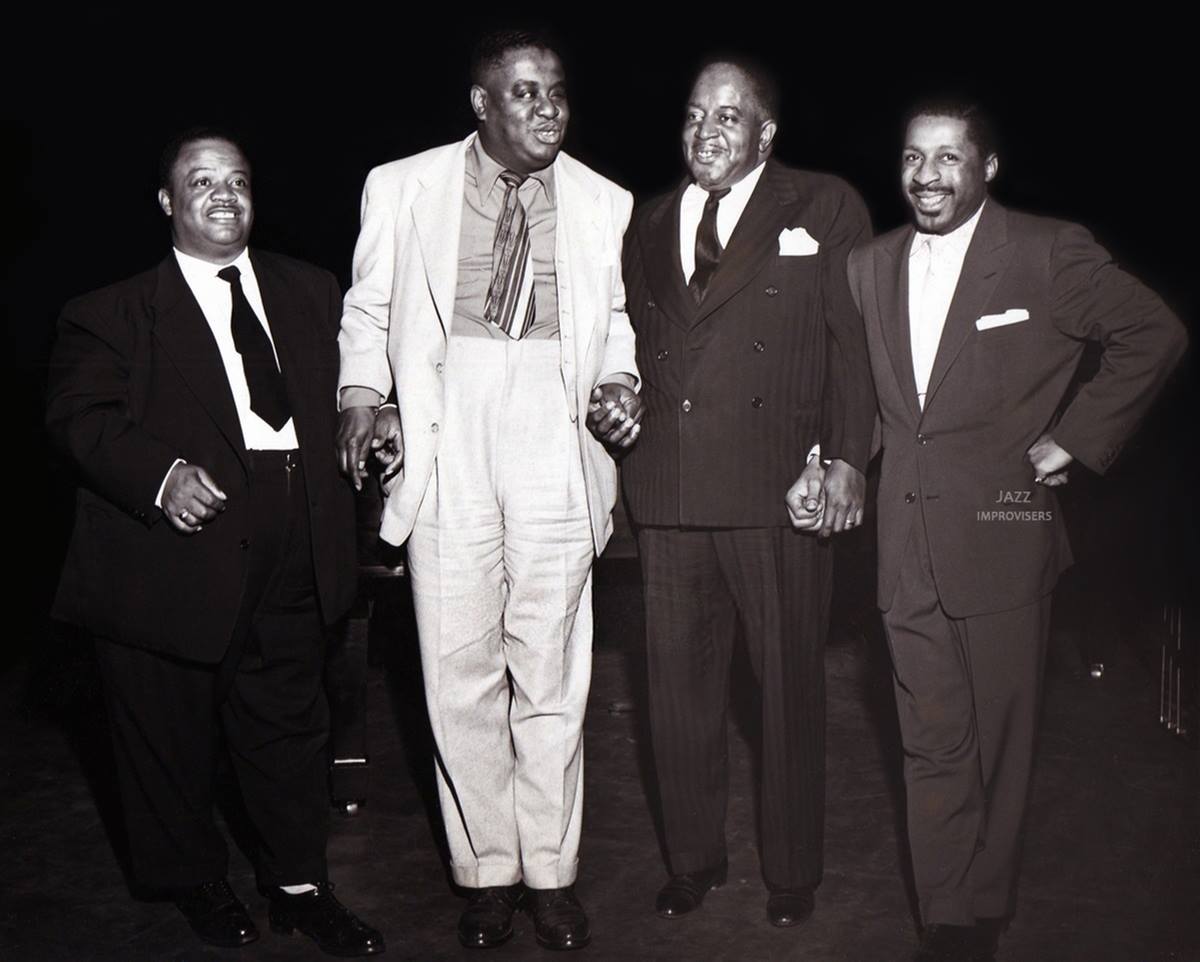

As an example of Chicago Blues, one needs not go any further than one of the most famous blues bands ever. Muddy Waters’ band with Little Walter, Otis Spann, Jimmy Rogers, and sometimes Willie Dixon. The gravity of this band remains so strong that bands today still make their livings in line with this Chicago-style path.

Boogie-Woogie Blues

Among the most loved sounds are boogie-woogie blues. Apart from the mention of Otis Spann and the ragtime players, most of these blues forms have focused on guitar pioneers; however, boogie-woogie blues is a genre rooted in piano players. It’s probably reasonable to wager that boogie-woogie piano originated around New Orleans. At the turn of the century, from the late 1800s to the early 1900s, the metropolitan quality of New Orleans, mixing European cultures of piano technique alongside African-American cultures of early blues, resulted in a kind of primordial soup that historians say gave birth to ragtime and boogie-woogie blues. Creole people, who had both Spanish descent and African-American descent, are suggested to have really pushed these styles forward since they had exposure to both cultures.

Boogie-woogie is characterized by that stomping, bassline riff that rocks back and forth at pulsating, powerful tempos. In terms of technicalities, it’s usually based on a power chord with one of the chords’ notes toggling back and forth between a few other notes, which adds a melodic side to the riff. To be quite honest, forget the silly theory that rock n’ roll was created by Elvis, Ike Turner, or even Louis Jordan. Just listening to boogie woogie blues, such as old recordings by Pete Johnson, Albert Ammons, Meade Lux Lewis, Art Tatum, James P. Johnson, and so on (as well as guitar players such as Tampa Red), it’s evident that not only is there no discernible difference between Tampa Red’s boogies in the 1920s and Bill Haley’s boogies in the 1950s, but it’s strikingly evident that this sound which we call Boogie Woogie or Rock n’ Roll was around at least in the 1920s and probably before recording technology developed in the late 1910s. That is to say, Rock n’ Roll existed probably in the 1890s, even. As piano players really championed this style, guitar players like Tampa Red, Blind Lemon Jeffersion, and Robert Johnson played that boogie line on guitar. Much later, Chuck Berry, Keith Richards, and just about guitar player has played those lines too.

An extraodinary example of Boogie Woogie blues is captured in a video of Albert Ammons playing the Swanee River Boogie, which is a great way to dig into the roots.

Capping Things Off

In summary, those are some of the archetypal styles of blues. The nearly untraceable styles, such as Delta Blues, which go back before good documentation started, up to the later styles like Chicago Blues. In the end, much of this is certainly up for debate, since one person may define a genre slightly different than another. It’s certainly important to have common ground in how to name these genres, but in the end it makes no difference to the actual songs! So again, these categorizations are really just that — artificial names that have no real bearing on the music, so they should be taken with a grain of sale while the music itself is enjoyed.